Troubling topsight

From maps to models.

How likely? How soon? What impact?

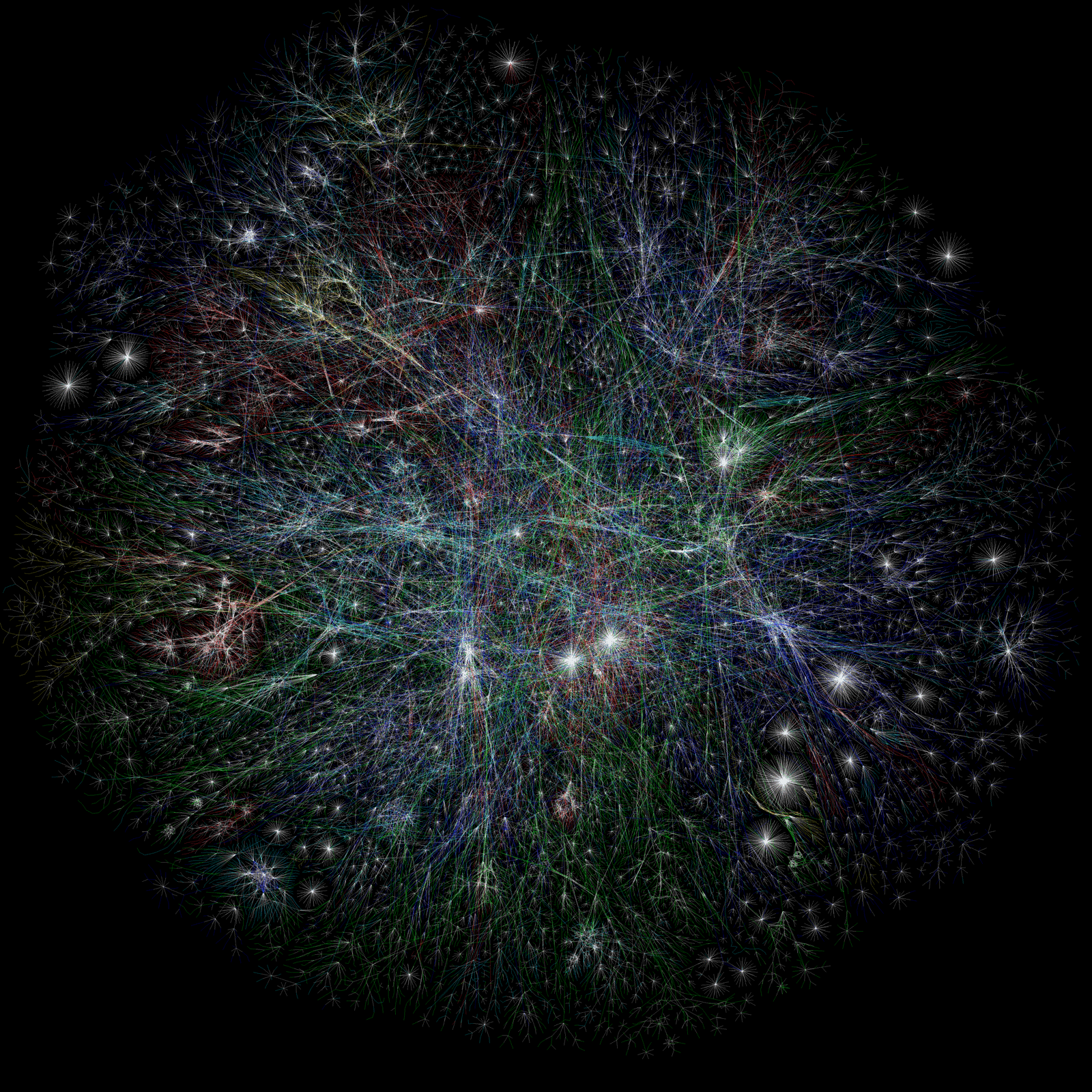

The archetypical portrait of a smart city is a control room. But even as critics and citizens alike have dismissed these anachronistic Apollo-era images, we're moving closer to the synoptic view of cities these facilities promised. Over the next decade, we'll see a marked shift, from city dashboards that provide static snapshots of how we're doing, and where we're headed, to constantly updated, panoramic views. Graphs, charts, maps, simulations, and 3D models will come to life and become more accessible to a broader variety of stakeholders.

This was all predicted. In the 1990s, computer scientist David Gelernter called this perspective "topsight... what comes from a far-overhead vantage point, from a bird's eye view that reveals the whole—the big picture; how the parts fit together." After decades of anticipation, as digital twins mature to capture more detailed, vital functions of cities in real time, we may soon achieve topsight. Public sector decision-making will become more informed by data, algorithmic analysis, and the ability to rapidly test and evaluate designs and policies.

But will this powerful new perspective actually improve how we govern cities? Will it lead to better or more contested decision-making? How will organizations and political structures respond to these new sources of authority and information, and to ways of working and governing? What's clear is that our expectations about how topsight can be used to predict and design the future are growing. But without a corresponding expansion of tools for visualizing and interacting with these models, we could be overwhelmed with data-driven insights.

Signals

Signals are evidence of possible futures found in the world today—technologies, products, services, and behaviors that we expect are already here but could become more widespread tomorrow.

..png)